Chuck Penner, Owner, LeftField Commodity Research

THE 2021 DROUGHT has a long tail. The extremes of 2021/22 had long-lasting impacts on the market that are hanging on. Bad experiences with grain contracts that year are causing farmers to view 2023/24 contract offers with more caution and scrutiny. And how well crops performed under 2021 drought conditions continues to be part of the 2023 crop decision process, especially in parts of the prairies that are still dry.

One of the biggest impacts of 2021/22 on markets has been the change in price expectations. Even though most realize the extreme highs of that year won’t show up again (without another drought), there seems to be an idea (not just among farmers) that new price ranges are in effect. Of course, prices will always cycle up and down, but it’s expected that this will happen at higher levels than before the drought.

It may be too soon to conclude that this is a new era, but these higher price expectations have created “floor prices” as farmers tend to stop selling if prices slide too far. As such, these expectations can be partly self-fulfilling. And of course, the rising cost of producing a crop means higher returns are needed.

This hangover from the 2021/22 marketing year doesn’t just affect marketing the 2022 crop; it’s also having an effect on acreage decisions for 2023. While prices are only one factor in the decision-making process, price performance after the 2021/22 highs is certainly a strong influence.

This hangover from the 2021/22 marketing year doesn’t just affect marketing the 2022 crop; it’s also having an effect on acreage decisions for 2023. While prices are only one factor in the decision-making process, price performance after the 2021/22 highs is certainly a strong influence.

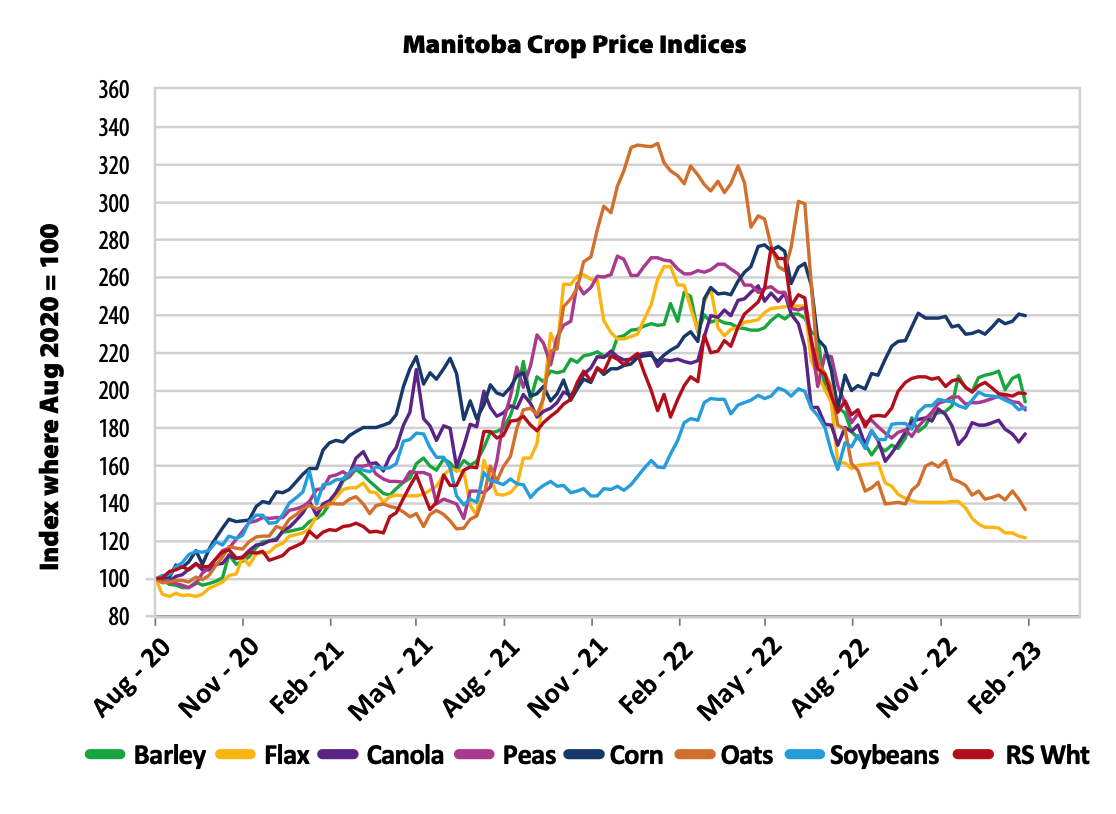

The Manitoba Crop Price Indices chart is busy, but shows all kinds of interesting information. For example, the upward trend in prices started in August 2020, making it clear that all crop markets

were strengthening well before the 2021 summer drought. Of course, that’s when prices for most crops really took off.

Compared to August 2021, oats were the superstar of 2022 but peas also performed very well. Meanwhile, soybean prices didn’t respond to the drought in Western Canada as prices were largely determined by events in the U.S., South America, and China.

When it comes to the 2023 acreage outlook though, one key factor is the resiliency of prices after the 2021/22 highs. The strongest performer appears to be corn, while soybeans and peas seem to be holding their own. On the other hand, oats and flax seem to be the weakest.

Unfortunately, dry bean bids in Manitoba are a little scarce, but bids from south of the border show a similar pattern as the chart above. Prices already started to climb in 2020/21 with the sharpest rise in the summer of 2021 as the drought persisted. Prices remained at those highs for months and only started to slide closer to the harvest of the 2022 crop. Even with this decline, dry bean bids have remained well above the market prior to the drought.

As mentioned, price is only one component in the decision process. Crop rotations need to be maintained, which limits the acreage shift between crops.

How a particular crop has performed agronomically the last couple of years can affect decisions. Some farmers are contrarians and decide to plant a crop when most others are moving away from that crop. And, planting a range of crops helps diversify returns and minimize risk.

New-crop bids are only starting to become available and will have an even greater influence on decisions. But as we look at how the crop options stack up against each other, our best guess is that 2023 pea acreage in Manitoba will be close to unchanged, while seeded area could slip in other provinces. Meanwhile, dry bean plantings could be slightly higher in 2023 but will need to compete with soybeans, which are also performing well.