Toban Dyck, Director of Communications, MPSG – Spring (March) Pulse Beat 2020

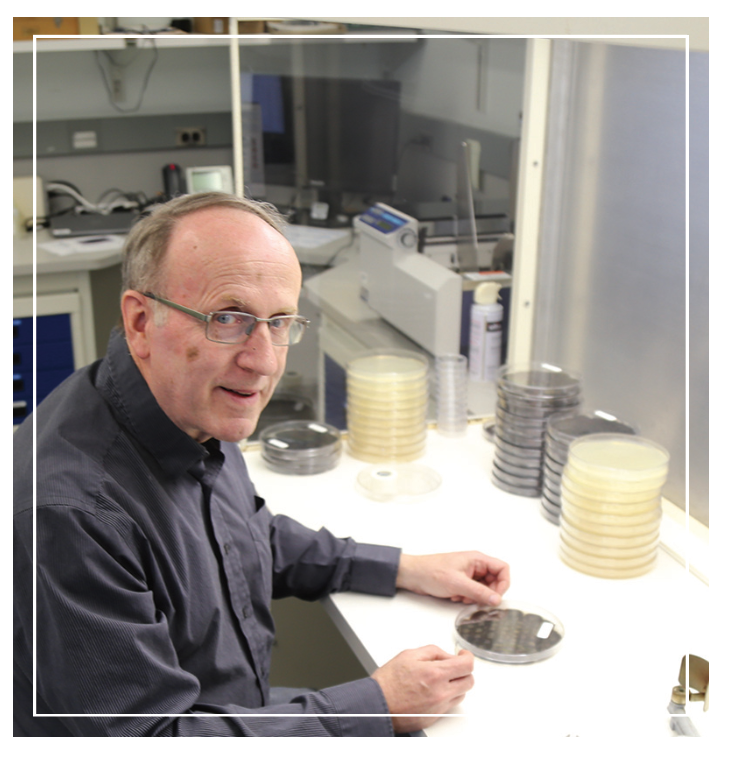

Dr. Robert Conner is a research scientist. His first computer was a TRS-80 (look it up). He volunteers at the Pembina Valley Humane Society, where he earned the trust and friendship of Simon, an abused rescue dog that arrived terrified and distant. And Dr. Conner was instrumental in revolutionizing the bean industry and he will be retiring this year.

“I’ve been with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada for 38 years and I turned 65 last fall, so I figured now would be a good time,” he said. “I’ve spent half my time at the Lethbridge Research Centre – 19 years there and it’ll be slightly over 19 years here (Morden, Manitoba) by the time I retire.”

It was the ‘70s. University of Manitoba plant pathologist and professor Claude Bernier was teaching a third-year course in plant disease control. Conner thought it would be interesting. He took it, and then he took some more like it and then he forever changed Manitoba’s dry bean industry.

Anthracnose hasn’t been detected in years. Cultivars with resistance to common bacterial blight (CBB) are now available in several market classes of dry beans and new sources of white mould resistance are starting to enter the picture.

I spent two hours with Conner, but that wasn’t enough. A picture started to emerge of a man whose depth not only resided in his scientific contributions to Manitoba’s and Canada’s agricultural industries but also in his character.

Conner has worked closely with Manitoba Pulse & Soybean Growers (MPSG) over the decades. He even sat on MPSG’s board of directors in an advisory capacity for several years.

This article should be about science, but if I am to write about what I took away from my time, I’d be ignorant not to mention the fact that Conner is a role model of a human being. His responses to my questions were paced, thoughtful and had the gravity of someone who cares.

If it weren’t for my pressing, Conner would have happily spent the entire time talking about how the successes MPSG was attributing to him actually belonged to his colleagues, farmers and funding partners.

He views his contributions to agriculture as the result of relationships, collaborations and the steady march of scientific progress. I would add that his focused, inquisitive and dedicated mind played a pivotal role, as well.

I asked him to recount a eureka-moment in his distinguished career. His answer was unexpected.

“A few years ago, the Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology did a series of articles by senior plant pathologists and I was reading one by an old instructor of mine. He said he never had a eureka-moment. I found the same to be true. It’s an incremental improvement. I can’t think of anything specific where I knew that I had discovered something that nobody else had ever thought of.“

When Conner arrived at the Morden research station on April 2, 2001, anthracnose was at about its worst in navy and pinto beans.

How did you tackle anthracnose?

The late Allister Duncan, owner of Duncan Seeds in Manitoba, made a big impact on the bean-growing industry here in Manitoba. For a while, Duncan was coming to the research station every week to talk to us about the different ideas he had. We had an industry meeting in the early ’80s and he had a whole list of ideas seed companies should be doing to control anthracnose. I think all of the major bean-producing companies decided to follow his protocol.

He was probably in his 60s and he would go into the fields after they’d been swathed and inspect them for anthracnose. I’m sure in the long run, it meant that millions of dollars had been saved. Duncan was bouncing ideas off of me. He had the respect of everyone in the seed business, so it didn’t sound like someone from an ivory tower was coming up with solutions.

What has your research focused on during your time at Morden AAFC?

I’ve worked a lot on common diseases in beans. Recently, we’ve worked a lot on CBB. There are new sources of resistance to that disease that seem to be really effective and that’s our most widespread foliar disease, even when anthracnose was a problem. We still see the blight in almost every field.

Resistance has come from a related species called tepary bean. There are a number of genes in that species that breeders have been using, and some provide more complete resistance than others do, so we’ve been working with breeders to screen their material, to see which lines have a high yield and good resistance.

CBB can reduce your yields — especially in wet years — by about 25–35 percent and it discolours the seed, so it affects the market value of the seed you do harvest. It’s a big one. Beans are prone to quite a few diseases, but anthracnose and CBB are the big ones.

We’ve also been working with Debra McLaren at the AAFC station in Brandon on root diseases. She’s had a couple of post-docs working on molecular methods of detection for the various root rot pathogens. We’re hoping that this will enable farmers to bring in soil samples or root samples into a lab and they can be told what the risks are of growing a crop on that field.

They’re taking the same approach to soybeans and field peas, as well.

What are you most proud of in your career?

Because anthracnose was such a big problem when I came, we learned a lot about it in the first 10–12 years I was here. The breeders were really serious about trying to get resistant varieties for that. So, I’m quite pleased. And the fact that we could get resistance to CBB. The emphasis over the last number of years has been to combine resistance to both those diseases, because, from a yield standpoint, they are probably the industry’s biggest threat.

In the long run, root diseases may be a larger problem. The fungi that cause those diseases produce different kinds of spores that can survive in the ground for long periods of time and some of them have broad host ranges.

We have done some research in trying to identify sources of resistance and we have found some lines that are not entirely resistant but are not as bad as the worst varieties that are out there. That’s been gratifying.

I’m connected to people in Ontario, Saskatchewan and Alberta. I also received great support from Dr. Ken McRae, a statistician in Nova Scotia, several scientists in North Dakota and the wonderful, ongoing help from my two technicians, Waldo Penner and Dennis Stoesz. It’s been a really good group of people. It’s meant that we could get so much more done in a short period of time and help everybody. That’s been a real benefit.

What is your relationship with MPSG — first memories?

I was always impressed with MPSG. Back in those years, they were looking at establishing new markets in Mexico. There were several trade missions that went down to Mexico and I think our bean breeder at the time went down with them at least once and was able to connect varieties being developed in Morden with these new Central American markets.

The pulse tour here is always a treat. MPSG is a remarkable group.

What was your first computer and how has technology helped your discipline?

It was a TRS-80. It was a stand-alone thing. It was pretty rudimentary, but it was good to learn on. There was kind of a giant leap forward when computers became much easier to use. Statistical programs became much easier to run. In the old days, if you had just one incorrect word, the program would just shut down and you couldn’t do any more processing.

The same technology used to identify the coronavirus is being used to identify some of the pathogens that we’re working on. The only thing is going to be cost. When you have a huge pandemic, then you’re willing to spend a lot of money. Money becomes hard to find on diseases on what are considered minor crops.

Now, the rapid sequencing of genomes is so much better and so much cheaper.

Where do you think research dollars should go?

Programs like the Canadian Agricultural Partnership and Growing Forward have allowed us to match and sometimes triple the money we get from groups like, say, MPSG. I think the members of MPSG receive great returns on the money they have invested in the development of new dry bean cultivars with multiple disease resistance and the development of field peas with resistance to root rot.

I think we’re really going to see the benefits of this work in the coming years. People will be able to send in their samples and get a full idea of risks — rapid disease identification.

How has the discipline of pathology changed over the years?

It’s become much more rapid and precise. It’s getting better all the time. The kinds of studies they’re doing now are getting really complex — you almost need to google some of the terminology.

What are the big challenges in agriculture?

They are finding ways to improve yield, and they’ll need to find ways to be more sustainable. Pulses fit into that. One of the biggest producers of greenhouse gases is fertilizer production, so if you have plants that are efficient in fixing nitrogen, then that cuts down a lot in that regard and it makes pulses and soybeans a great choice.

We need better rotations and better understanding. There’s always a worry that new pathogens will surface or dormant ones will become active. If global warming is something that is happening, we could see things like new insects and diseases become more severe early in the growing season.

What do you enjoy doing when you’re not at work and what are you going to do when you retire?

I volunteer at the Pembina Valley Humane Society. I do chores twice a week. I go there on Wednesday and Thursday, after work and I close up the place on Saturday and Sunday. It’s been quite gratifying. You get your favourites and I’m always happy to see when a dog or a cat gets adopted.

Sometimes they come in and they’re frightened if they’ve been abused. We had this dog, Simon, who was terrified. He hid in a corner the first week he was there. I would always give him a treat. Now, after about three weeks, he’ll follow me outside and he sticks close to me. It’s been a real positive thing.

Also, lately, I have been studying my family history. I’ll take some time and put it all together. I’d like to do that.