How confident are you that your pea and lentil seed is not limiting yield potential before you even put it in the ground?

With rising acres leading to a shortage of certified seed, there are serious concerns about the quality of the seed that will be used this spring.

Sarah Foster of 20/20 Seed Labs joins our own Kelvin Heppner for this Pulse School episode, offering an in-depth look at pulse germination and disease testing, as well as physical and chemical seed damage.

If possible, buy certified seed. If that’s not an option, a germination test is the first line of defence against planting poor seed, she says.

Germination rates for both lentils and peas should exceed 80 percent — above 85 percent is preferred, explains Foster.

From there, she suggests having a fungal screen done to determine disease levels, showing an example of bin-run lentil seed testing positive for ascochyta, anthracnose and fusarium.

“Beyond five percent of ascochyta and anthracnose, I wouldn’t consider using it for seed,” says Foster. She recommends always treating seed, as the pathogens listed above — as well as others like pythium and aphanomyces — may not be present in the seed, but are likely hanging around in the soil.

Related: Top 5 Tips for a Great Lentil Crop

As she demonstrates, treating a highly-diseased sample will reduce infection but won’t make up for poor germination.

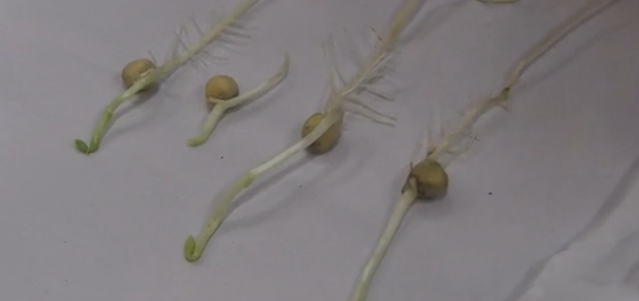

Using pea samples submitted to 20/20’s lab, Foster shows how mechanical damage from handling can reduce germination levels. Damaged seeds will leach sugars and starches, serving as a food source for pythium.

Pre-harvest weed control can also cause chemical injury to seed, which she explains often exhibits itself in short, thickened primary roots, with extra branching and firming of secondary roots.